The professor didn't follow up on our raised hands, as he assumed that our kitchens looked at least slightly better than his nightmare example. He asked us how we organized our shared living spaces – our domestic commons. Did we have cleaning schedules, or a penalty system? Many students answered affirmatively to the former question: our kitchens had cleaning schedules, and we had mutual agreements that regulated the use of our shared spaces. Beginning in the early 1970s, Nobel Prize-winning economist Elinor Ostrom broke with the dominant paradigms in economics and environmental science, which assumed that people were incapable of regulating their common property, and that regulation from above would always be necessary. (See Garrett Hardin's well-known essay, “The Tragedy of the Commons.”) Ostrom’s research on how different communities successfully managed common resources proved that under the right circumstances, groups of people can regulate a commons perfectly well by themselves.

Ostrom, E. (2015) Governing the commons. Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press

All photos in this story have been shot by Maartje Oostdijk. View the full series here.

Living together

De Klopvaart

De Klopvaart

De Klopvaart 'Centraal Wonen' is a type of communal living in which residents choose to share various facilities with one another and share the responsibility for their living environment. Centraal Wonen Klopvaart is a project that has been created for and by the residents. The ...

is one such example of a self-organized commons in Utrecht. De Klopvaart is an intentional community of around 85 adults and 15 children, and is located in the neighborhood of Overvecht, Utrecht. A number of adjacent apartment complexes around a shared courtyard offer an array of opportunities for ways of living that are interesting to (Un)usual Business' perspective and case studies. Although it doesn't show on the outside, the way people live together here differs radically from the individualistic uniformity of the other apartment complexes in the neighborhood. I talked to Dirk (29) and Hanz (60), who each have their own living space within the two different apartment complexes that constitute De Klopvaart.

What distinguishes an intentional community from the chaos of collective living in a student dorm? Dirk attributes it to 'commitment' – in his view, the people who join De Klopvaart are like-minded, which makes them more engaged. After becoming fed up with ‘the tragedy of the common’ rooms of his student house, Dirk began to look for a different way of living communally. While a student dorm places people together out of (economic) necessity, in an intentional community all members choose individually to live together with like-minded others. Even Dirk’s dorm's 'clothespin system' could not prevent 'phantom dishes' from piling up in the sink, and his housemates' nonchalance in regards to hygiene was tangible. While De Klopvaart has very few fixed rules, its members put time into it as they see fit to maintain the space. Although Dirk reports that there are few real obligations, he does feel that everyone is expected to contribute.

Physical spaces are where the rules and the means of sharing develop Stavros Stavrides (freely translated)

De Klopvaart contains four clusters of houses, and each cluster consists of three houses. Each house is divided differently into living units, and each has its own customs. When I ask Dirk which kinds of things or activities are shared, he answers: “mostly practical things,” primarily referring to the physical spaces of De Klopvaart. According to Greek architectural theorist Stavros Stavrides, these physical spaces are sites where the rules and the means of sharing develop, which makes them crucial to this story of a residential commons. Dirk's house, for example, shares a common living room and kitchen. As I follow Dirk through the common living room and kitchen, I observe that there is still a Christmas tree alongside a lot of furniture, many board games, and other toys. Dirk mumbles: “Yes, the living room is basically the family room.” The kitchen is tidy and clean, and contains many different sets of dinnerware contributed by the house's many different occupants. Hanz shares his kitchen with a younger man who lives on the same floor. He says it's like sharing the kitchen with his son. While I'm trying to take a picture of his tidy, cozy kitchen from the narrow space of the corridor, Hanz calls out from the living room that it is typical for such kitchens to contain two fridges. Acknowledging his point, I try as best as I can to frame both fridges in one picture.

Stavrides, S. (2016) Common Space: The City As Commons. London, Zed Books Limited

Compared to the kibbutz Hanz lived for 14 years, he says that living at De Klopvaart is 'child's play.' Here, his door can be locked for two weeks and no one will confront him about it, while the kibbutz, where his grown-up children still live, expects a lot more from its residents. On a kibbutz everyone has chores, members work together on household and agricultural tasks, and they collectively produce sustenance for the whole. And, in addition to collective child-rearing practices, everyone on the kibbutz earns the same income. Hanz is happy with this new community, where he has lived for some three to four years, although he sometimes lets some discontent show: some people at De Klopvaart contribute less than others and are not called out on it. “There are no sanctions. It's just accepted.”

(Un)usual Business note: Does everyone need to contribute the same amount of time, or share in the same kind of tasks to sustain a commons? Does there need to be some form of social control to ensure that people contribute enough?

Later in our conversation, Hanz provides some nuance to these earlier statements. Supposedly, around 15% of the members contribute less than is expected of them. He also adds that over the years some people have appropriated more than is fair. “Some occupants have appropriated more than others over the years. That can be a cause of conflicts.” Such people may put their mark on common property more than others, take up more physical space than others, or do fewer of the shared chores. There is no established procedure for dealing with this discrepancy. At most, you can file a complaint with the board. While none of the examples Hanz mentions are serious, they are sometimes the primary reason for a person to move into a different house within De Klopvaart, or to leave the community entirely.

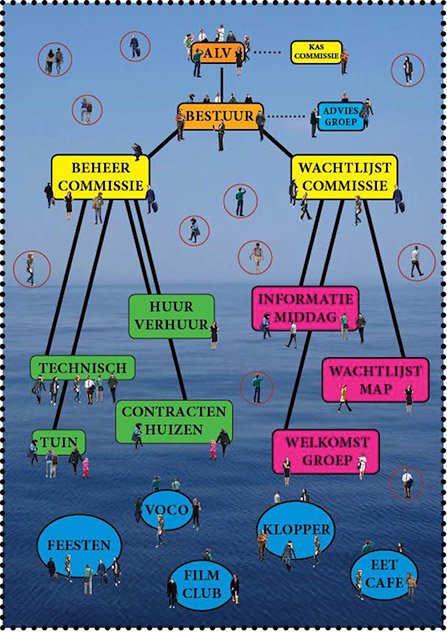

Legally, the community is registered as an association, and everyone who decides to live at De Klopvaart is expected to join a commission. Figure 1 shows the structure of the many different commissions within the community. When the community was founded in 1984, there were only two commissions: one for administration and one to manage the waiting lists. As the community grew, the structure was expanded; a commission for leasing and renting was added, as well as one to organize an information day for interested people. There are also commissions that are less affiliated with the logistical tasks of the original two, such as the food collective (VoCo), of which Dirk is a member. As part of the magazine commission, Hanz publishes ‘de Klopper' three times a year, and the publication is mainly filled with stories from residents. There is both a common garden area and project room, each of which are managed by their respective commissions.

Figure 1: The structure of the many different commissions within the 'de Klopvaart' community

Dirk gives me a short tour of the VoCo shop. They don't sell fresh vegetables or fruit, but all of the products are organic: crackers, rice cakes, quinoa, and more. Dirk points out a give-away shelf, and the Christmas packages they made for all the volunteers. Pumpkins are spread out on the ground, with the names of the volunteers and a thank-you card.

The community has its own organizational structure, with several levels of organization. The commissions have their own rules to ensure that the shared spaces (VoCo, the project room, and the garden) are kept clean and treated respectfully. On a higher level, the board communicates directly with the buildings’ owner, Portaal, while the advice group, in turn, advises the board. Three times year a general meeting is held for all members, in which every adult resident has a voice. Hanz says only about one third of occupants participates in these meetings.

Hanz describes one example of a topic that might come up during these meetings – the association collectively uses a green/environmentally conscious energy provider, but one of the apartment complexes was clever enough to sign a different, cheaper contract. This action violated the association's statutes, making it illegal. If every house wanted to make this decision for itself, the statutes would first have to be adjusted by a notary, and this would be quite pricey.

Hanz talks skeptically about a group of residents who are working on the topic of social cohesion. This group convened to work on improving the social cohesion and relations within the community. Dirk and Hanz agree that there are not many common activities for the whole community: a film screening every two weeks, a food café six times a year, a garden party every now and then, and sometimes people organize gatherings for the holidays. New Years and Sinterklaas, for instance, are sometimes celebrated together.

Potential newcomers can visit De Klopvaart during an information day where they can sign up to be put on a waiting list. Usually, the commission in charge of it aims for a waiting list of around 70 interested people. When a house has a vacancy, they get the folder with the list of candidates and select the people that they like. The next step is to invite these candidates for a visit to get acquainted with the specific houses with a vacancy. On average, five new people join every year, and every new tenant signs an individual contract with Portaal. In this respect, the process works similarly to most other housing situations, with only the democratic principle as the differentiating character. In a regular rented house, tenants do not get to decide who their neighbors are, and maintenance of any shared spaces is often outsourced.

When I ask Hanz why people leave De Klopvaart, he mentions two main reasons. First, there are tensions and discontent among fellow tenants – i.e., conflict. The second reason he mentions has to do with relationships and family composition. Some residents want to move in with their partner, or don't want to raise children in an intentional community.

Dirk is very content with his decision to live at De Klopvaart. After travelling through Southern Europe and Morocco and doing a lot of volunteer work here – both for intentional communities and for other projects – he was looking for a place in Utrecht to live communally and less passively, but also to escape his more traditional student housing situation. Walking around De Klopvaart, it appears that the 15% who don't contribute enough according to Hanz don't leave much of a mark on the community. The houses look orderly, cozy, and clean to me, and the verdant and deliberate garden is in stark contrast to the one in my own student house, which is full of weeds and discarded furniture. On the other hand, in the De Klopper magazine an ex-tenant indicates that she is glad to part with the unmaintainable and weed-filled garden, as well as with her noisy neighbors. She is moving in with her boyfriend – just the two of them – on a regular street with families and comfortable contact with the neighbors. Although there are still strides to be made in terms of community spirit and organization, De Klopvaart does offer a very livable and harmonious environment. It is certainly different from my messy student house. Still, sharing common property always involves more compromise than living on your own. Fortunately, De Klopvaart offers its occupants many other advantages, and for now Dirk and Hanz have no plans to leave the community.

All photos in this story have been shot by Maartje Oostdijk. View the full series here.

This article was published in the (Un)usual Business journal Utrecht Meent Het #2 (September, 2016).