Political scientist and economist Francis Fukuyama argued in 1992 that with the end of the Cold War we were witnessing the “end of history” and “the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” However, Hugo Chavez, the former socialist president of Venezuela, replied in 2006 with: “The end of history was a totally false assumption, and the same was shown about Pax Americana and the establishment of the capitalist neo-liberal world. It has been shown, this system, to generate mere poverty. Who believes in it now?” In other words, the universalization of liberal democracy, of capitalism itself, is debatable.

Markets, a Modern Invention

In times of economic crisis a certain nostalgia seems to emerge, which is not totally irrational. As current western market societies often fail to guarantee their citizens even the right to live—a right that was granted even by feudal institutions centuries ago—historical research makes sense. We may find forgotten institutions from the past—perhaps non-market mechanisms—which can be of some use to today's problems. Not surprisingly, books about economic history are more popular than ever among those critical of the status quo. Debt: The First 5000 Years(2011), a book by anarchist anthropologist David Graeber is extremely popular with those involved in the Occupy movement for instance.

This renewed interest in economic history can only be applauded, because accounts of economic history as provided by Graeber—exposing elements of history which are too often forgotten—tackle the widely-held myth that humans have always lived by market principles, bartering goods and services for individual gain and profit.

Economic history shows that markets did not emerge “naturally”, but were often imposed from above with serious resistance from below during the last two to three centuries. As economic historian and anthropologist Karl Polanyi concludes in the closing chapter of The Great Transformation which was first published in 1944:

Economic history reveals that the emergence of national markets was in no way the result of the gradual and spontaneous emancipation of the economic sphere from governmental control. On the contrary, the market has been the outcome of a conscious and often violent intervention on the part of government which imposed the market organization on society for noneconomic ends.

What’s more, economic history also show that market discipline was never introduced universally, but in a dual manner, as linguist/philosopher Noam Chomsky explains: “market discipline for the weak, but the ministrations of the nanny state, when needed, to protect the wealthy and privileged.” We can still see this dual manner today, as bankrupt banks are bailed out by states with trillions of dollars, while bankrupt families are evicted from their homes and social services are lowered, imposing a market discipline on citizens while providing generous welfare schemes for the financial sector.

Those who dare to question this status quo and question the “end of history”, should come up with some alternative. Not necessarily a blueprint, but at least some guiding principles on which the alternative(s) will be based. I argue that the guiding principles for any alternative should be justice, democracy, and liberty.

Firstly, though market societies have many flaws, not all their current institutions are useless. Take social safety nets, public housing, healthcare, and education for instance. Though these programs suffer from corruption, mismanagement, and inefficiencies, they still provide citizens with basic services necessary for survival. Reform them, yes! More transparency, of course! Democratize them, as soon as possible! But there’s no need to abolish them.

Secondly, to open up our imagination some more, we should study our economic histories, not to consider all pre-capitalist institutions superior to our own, but to carefully judge them both on fairness and feasibility in today’s context. I argue that especially the commons—the collective ownership and management by local users of shared resources—is a pre-capitalist institution which can be of use to us today. Furthermore, we could view “commoning” not only as a temporary survival strategy when market societies fail to provide people enough employment and economic security, but as a viable alternative to the capitalist enterprise and the market mechanism itself.

Before Markets: Commoners, Priests, and Feudal Lords

Let’s take a look at how humans governed their production and distribution in pre-capitalist days, when the role of markets was “no more than incidental to economic life,” according to Polanyi. It was a time when “custom and law, magic and religion co-operated in inducing the individual to comply with rules of behavior, which, eventually, ensured his functioning in the economic system.”

To summarize Polanyi’s account of pre-capitalist economies, they were governed by a variety of institutions. Some were based on symmetry (communities exchanging goods and services on the basis of reciprocity), some based on centricity (churches and kingdoms), and some on autarchy (households producing for themselves), but the market principle was largely absent and the motive of gain was “not prominent”.

The commons were mostly based on the principle of symmetry, but they were not separate from churches and kingdoms, as historian Tine de Moor describes in a case study of a common in Flanders, which existed between the sixteenth and eighteenth century; the registration of its members was administered by the local priest and commoners were taxed by a local lord. However, for the rest of their activities “the common functioned autonomously.”

Until now I’ve emphasized the need to research economic history, as if the commons can only be found in history books. However, in today’s more traditional societies (perhaps it is better to say: the less industrialized ones) there are still commons which have survived the expansion of global capitalism. Political economist Elinor Ostrom won a Nobel Prize in economics in 2009 for researching these commons and codifying many fieldwork studies of what she calls “common pool resources”—collectively owned lakes, forests, water basins, or fish stocks. Ostrom finds that even today, mostly in less industrialized countries, many local communities are perfectly capable of managing common property with a huge variety of non-market mechanisms, with little or no state interference, and in a sustainable way—avoiding overconsumption. As long as local users are able to communicate with each other and there is some level of trust among local users, people are often perfectly capable of resolving conflicts about common property through dialogue without interference of the state or the market. Her findings go directly against the famous argument of ecologist Garrett Hardin, that “freedom in a commons brings ruin to all” and that states or markets are needed to govern all resources.

We should not be too romantic about the commons, Ostrom argues, but acknowledge that there is something more than markets and states. Communal property regimes are no panacea, but are often sustainable solutions to local problems. Ostrom does not deny that “freedom in a commons” can create some conflicting interests—as people might want to fish in the same water at the same time—but she observes that people are often perfectly capable of solving conflicting interests through dialogue and in maintaining a level of trust.

Compatibility

Is the modern world too complex for the commons?

If we have been perfectly capable of managing economies without market-mechanisms in the past, as Polanyi argues, and as we haven’t lost that capacity yet, at least in the less industrialized societies, as Ostrom observes, the question arises as to why markets and states have become so dominant at the expense of the commons. Is it because non-market institutions are incompatible with the complexity of modern societies? Polanyi would object:

It should by no means be inferred that socioeconomic principles of this type are restricted to primitive procedures or small communities; that a gainless and marketless economy must necessarily be simple. The Kula ring, in western Melanesia, based on the principle of reciprocity, is one of the most elaborate trading transactions known to man; and redistribution was present on a gigantic scale in the civilization of the pyramids.

In short, Polanyi finds throughout pre-capitalist history that local communities were not isolated from each other but were often well connected economically through various kinds of central redistribution mechanisms, some more democratic, some more tyrannical. And as Ostrom observes among the surviving commons of today: “When a common-pool resource is closely connected to a larger social-ecological system, governance activities are organized in multiple nested layers.” The point is: even larger complex economic systems have been able to function without any significant reliance on states or markets.

Did people favor the marketization of their land and labor?

Another hypothesis which can be discarded is that people simply chose to abandon the commons and favored the market mechanism and its private property regime. Historian Peter Linebaugh looked into this question. His account of the emergence of the market economy in England tells us that the market discipline was introduced with quite some difficulty from above, meeting serious resistance from below. After all, common lands had to be privatized, fenced off and in this way shut off from the people who relied on them for their subsistence, in order to establish a market for both land and labor. It is not surprising that many people didn’t agree with this policy.

These privatizations of common lands became known as “enclosures” and were occurring in various western countries around the same time. In an interview, Linebaugh explains how this enclosure movement was not limited to common lands but affected every aspect of society:

There were many types of enclosure but when we refer to the English enclosure movement, it’s parliamentary form occurred really between 1760 and 1830, that is at the time of the French, Haitian, American revolutions. And it put common land . . . it privatized the land of England. One of the great historians of enclosure, Jeanette Neeson, refers in a powerful phrase to the “closing of England”. She imagines England as being the land, and the land was shut off from the people by fences, by hedges, by ditches, by no-trespassing signs, by even mantraps, to prevent access to land which formerly had provided subsistence resources for commoners. So the enclosure movement is really a destruction of the commons.

The force and violence of the enclosure movement is also emphasized by Polanyi:

Enclosures have appropriately been called a revolution of the rich against the poor. The lords and nobles were upsetting the social order, breaking down ancient law and custom, sometimes by means of violence, often by pressure and intimidation. They were literally robbing the poor of their share in the common, tearing down the houses which, by the hitherto unbreakable force of custom, the poor had long regarded as theirs and their heirs’. The fabric of society was being disrupted; desolate villages and the ruins of human dwellings testified to the fierceness with which the revolution raged, endangering the defenses of the country, wasting its towns, decimating its population, turning its overburdened soil into dust, harassing its people and turning them from decent husbandmen into a mob of beggars and thieves.

So with violent enclosures the commons disappeared and a market discipline was imposed, though in a dual manner of course as Chomsky explains, “market discipline for the weak, but the ministrations of the nanny state, when needed, to protect the wealthy and privileged.” The hypothesis that society freely chose or naturally evolved towards a (dual) market society is not only theoretically difficult to believe, but refuted by several historians.

Was commoning incompatible with technological progress and industrialization?

What Linebaugh calls commoning and what Ostrom calls common pool resources mostly refer to local, natural resources like lakes, water basins, and forests. It is tempting to conclude that the “primitive institution of the common” is simply bound to disappear when societies industrialize and adopt modern technologies. After all, the commons nowadays only exist in more traditional, less industrialized societies. In industrialized societies, the capitalist, hierarchical enterprise became the dominant form of production, with control over work separated from ownership (as workers don’t own their factories/offices) and with a minute specialization and rigid division of labor. Assuming competitive markets, in which the most efficient production methods survive, it follows that the capitalist organization was more efficient than communal property systems. This implies a trade-off between economic efficiency and communal values, between highly productive capitalism and living like the Amish.

If we define anything that is communal property as a commons, including worker-owned cooperative workplaces, than this hypothesis simply does not hold. Linguist Noam Chomsky discusses this alleged inverse relation between equality and efficiency, another widely-held myth in the field of economics:

[C]onsider the widely held doctrine that moves toward equality of condition entail costs in efficiency and restrictions of freedom. The alleged inverse relation between attained equality and efficiency involves empirical claims that may or may not be true. If this relation holds, one would expect to find that worker-owned and -managed industry in egalitarian communities is less efficient than matched counterparts that are privately owned and managed and that rent labor in the so-called free market. Research on the matter is not extensive, but it tends to show that the opposite is true. Harvard economist Stephen Marglin has argued that harsh measures were necessary in early stages of the industrial system to overcome the natural advantages of cooperative enterprise which left no room for masters, and there is a body of empirical evidence in support of the conclusion that “when workers are given control over decisions and goal setting, productivity rises dramatically.”

Marglin’s research is extremely relevant here. The case he made in his 1974 paper “What Do Bosses Do?” is that, in the course of English industrialization, the capitalist firm did not gain its victory over the worker-managed workplace because it was technologically superior or more efficient, but because those who stood to gain by the capitalist organization of production had the political power to make their preferred model win. For instance, one helpful policy was the patent system, which “played into the hands of the more powerful capitalists, by favoring those with sufficient resources to pay for licenses (and incidentally contributing to the polarization of the producing classes into bosses and workers).” This patent system, Marglin explains, created a “bias of technological change towards improvements consistent with factory organization” and “sooner or later took its toll of alternatives.” So not only did the political power of capitalists ensure that new technologies were applied to increase their power over labor, but their political power biased the progress of technology itself in their favor. To conclude, in Marglin’s own words:

It is important to emphasize that the discipline and supervision afforded by the factory had nothing to do with efficiency, at least as this term is used by economists. Disciplining the work force meant a larger output in return for a greater input of labor, not more output for the same input.

Alternatives

Now I have argued that the common lands and lakes disappeared, not because people freely chose to replace them with market and state forces but through political violence. I have argued that commoning did not come to dominate western industries during industrialization (through worker-owned cooperative workplaces), not because the capitalist firm was technologically superior or more efficient, but because the capitalists simply had more political power. The commons disappeared because of politics, the result of human actions, not because of some inevitable exogenous cause beyond the scope of human influence.

Don’t take my word for it. We are in the field of social sciences, not physics, and my interpretation of history is as biased as any other. We are entering even more shaky grounds when discussing alternatives: alternative courses of history, or alternative futures.

Could the destruction of the commons have been prevented? Different points of view are possible. According to Polanyi, the “primitive institution of the common” was simply bound to disappear and people could at best slow down the rate of change, which was “often of no less importance than the direction of the change itself,” for it allowed the “dispossessed” more time to “find new employment in the fields of opportunity indirectly connected with the change.”

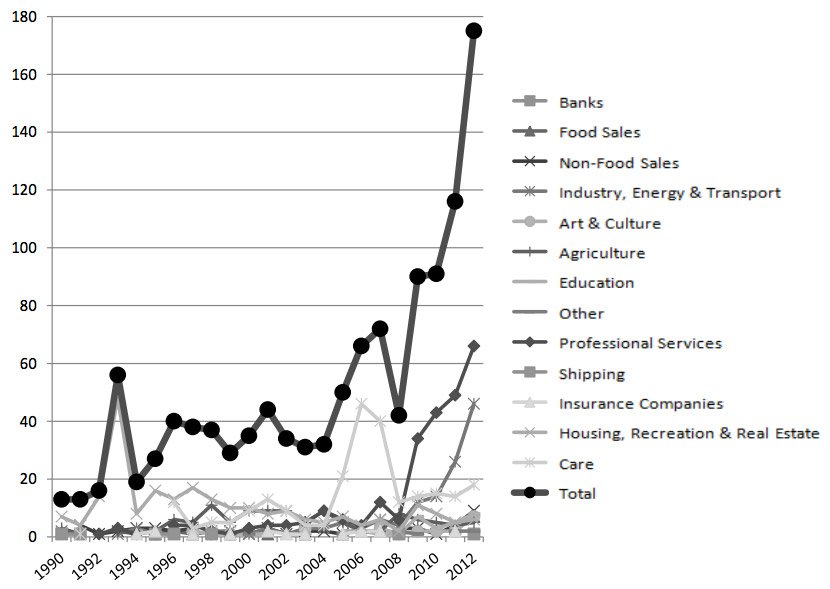

Another point of view is that we, in western industrialized nations, can at best enjoy the occasional reemergence of the commons, as research from De Moor suggests. What De Moor finds is that throughout history periods of liberalization and marketization are often followed by periods in which many new “institutions for collective action” emerge—bottom-up initiatives of citizens where “cooperation and self-regulation form the jumping-off point for daily practice,” more or less in the tradition of the commons. De Moor noticed a strong growth in “collective action” following the first market developments during the Middle Ages and after “a strong wave of liberal thinking and privatization in the nineteenth century” and even today (figure 1) “after the privatization of public services—neoliberalism—in the last decades of the twentieth century.”

This occasional reemergence is only logical as markets and states often fail to provide people enough employment and economic security to survive, forcing them to rely on each other through commoning as temporary means of survival, until they are offered employment again.

A more radical stance would be to argue that commoning should be the fundamental institution of our society. You are then entering the field of the radical left. Note that it was the tradition and memory of the commons that partly laid the foundations of many important left-wing ideologies, from anarchism to communism. Karl Marx himself, Linebaugh explains, wrote that “expropriations of commons were what first sparked his interest in economics or material questions, referring to the criminalization of a commoning practice in the Moselle river valley near Trier (where he was born).”

Figure #1: Evolution of the number of new cooperatives per sector from 1990 to 2012

The radical question is whether commoning—perhaps in combination with certain elements of our welfare states—can be relied upon, not only as temporary means of survival under disruptive market forces, but as a fundamental institution of our modern societies, replacing the market-mechanism to a large extent.

Like Marx, Chomsky, or Linebaugh, there have always been many thinkers who dared to imagine alternative “directions of change”, arguing that not only the rate of change but the direction itself depends on human will. Neither the field of economics, nor history itself, has ever proved them wrong.

Francis Fukuyama, "The End of History?," The National Interest (Summer 1989): p. 2.

Hugo Chavez, “Chavez Address to the United Nations,” (speech, United Nations, NY, 20 September 2006).

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001), p. 250.

Noam Chomsky, Chomsky on Anarchism (Oakland: AK Press, 2005), p. 206. Not surprisingly, as economist Ha-Joon Chang laments, economic history does not receive much attention within mainstream economics classes. On the contrary, “economic history courses have been disappearing from classrooms across the world. Once a compulsory part of economics education, they have been relegated to the remote corners of ‘options’ and even closed down.” [(Ha-Joon Chang in Edward Fullbrook, eds., A Guide to What's Wrong with Economics (London: Anthem Press, 2004), p. 279)].

See Kenneth Haar, “Stop listening to banks,” Corporate Europe Observatory, 10 April 2012: “Combined, the 27 member states of the EU have (by October 2011) set aside 4.5 trillion euro for support, guarantees and loan packages to banks, or almost double the annual GDP of Germany,”.

“Commoning” as a verb, was coined by historian Peter Linebaugh in 2011. See Julie Ristau, “What is Commoning, Anyway?” On the Commons (March 2011).

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001), p. 43.

Tine De Moor, “Participation is more important than winning, The Impact of Social-Economic Change on Commoners’ Participation in 18th-19th-Century Flanders,” Continuity and Change 25, no. 3 (2010): p. 411.

See a summary of Elinor Ostrom’s body of work in her Nobel Prize lecture, “Beyond Markets and states: Polycentric Governance of complex economic systems” (Nobel Prize lecture, Stockholm, 8 December 2009).

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation, pp. 49–50.

Elinor Ostrom, “Beyond Markets and states: Polycentric Governance of complex economic systems,” p. 422.

Historian Tine De Moor points out that the privatization of common lands occurred in various European countries around the same time. Tine De Moor, “Homo cooperans. Institutions for collective action and the compassionate society,” (lecture, Utrecht University, Utrecht, 30 August 2013).

Interview with Peter Linebaugh. “Enclosuse, Luddism and Magna Carta,” from an interview on Against the Grain Radio, 6 May 2013.

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation, p. 35.

Noam Chomsky, Chomsky on Anarchism (Oakland: AK Press, 2005), p. 206.

As one book on the Amish explains: “The Amish anti-individualist orientation is the motive for rejecting labor-saving technologies that might make one less dependent on community.” Logan Drake, Life of the Amish. (Mainz: Pediapress, n.d.), p. 8.

Noam Chomsky, “Equality: Language Development, Human Intelligence, and Social Organization,” in The Chomsky Reader, ed. James Peck (New York: Pantheon, 1987), p.185. Chomsky also mentions another relevant piece of research in writing that the studies of David Noble in his books Progress Without People: New Technologies, Unemployment, and the Message of Resistance (Toronto: Between the Lines, 1995) and Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984) show that post-WWII automation and computer control of machine tools “could have gone either direction; the technology that was available could have been used to increase managerial control and de-skill mechanics, which was done, or it could have been used to eliminate managerial control and to put control into the hands of skilled workers. The decision to do the first and not the second was not based on economic motives, as Noble points out pretty successfully, but was made for power reasons, in order to maintain managerial control and a subordinate workforce,” introduction to Anton Pannekoek’s Workers’ Councils (Oakland: AK Press, 2003), ix.

Stephen A. Marglin, “What Do Bosses Do?" Review of Radical Political Economics (Summer 1974): p. 94.

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation, p.37.

Tine De Moor, “Homo cooperans. Institutions for collective action and the compassionate society,” p. 18.

Peter Linebaugh, “MEANDERING ON THE SEMANTICAL-HISTORICAL PATHS OF COMMUNISM AND COMMONS,” The Commoner (December 2010): p. 2.

This article was published in the (Un)usual Business Reader (2013)