Its premise is a desire to change the capitalist rule stipulating how we run our households, organizations, and lives—one that demands we compete, if not exploit, own, and accumulate. Today, intellectual, creative, and manual laborers are all affected by the violent excess of such rule. This is typically manifest in the permanent state of being “busy” that dominates our social relations and reduces our joi de vivre. We also find ourselves laden with anxiety from precarity and monetary indebtedness (a new form of slavery?) that the aforementioned rule perpetuates for its own survival. On the other side, this condition is brought to a boiling point by the enveloping policy of austerity in the fields of care, culture, and education, alongside the racist policy of migration. (Un)usual Business looks for an alternative to the status quo through studying together within and outside of institutions under the conviction that alternatives are already being practiced. Given that Utrecht is the base of most (Un)usual Business members, and also due to the prescient commoning activity of the city’s communities, we examine the context of Utrecht and its practices which we could recognize as those of the commons or community economies.

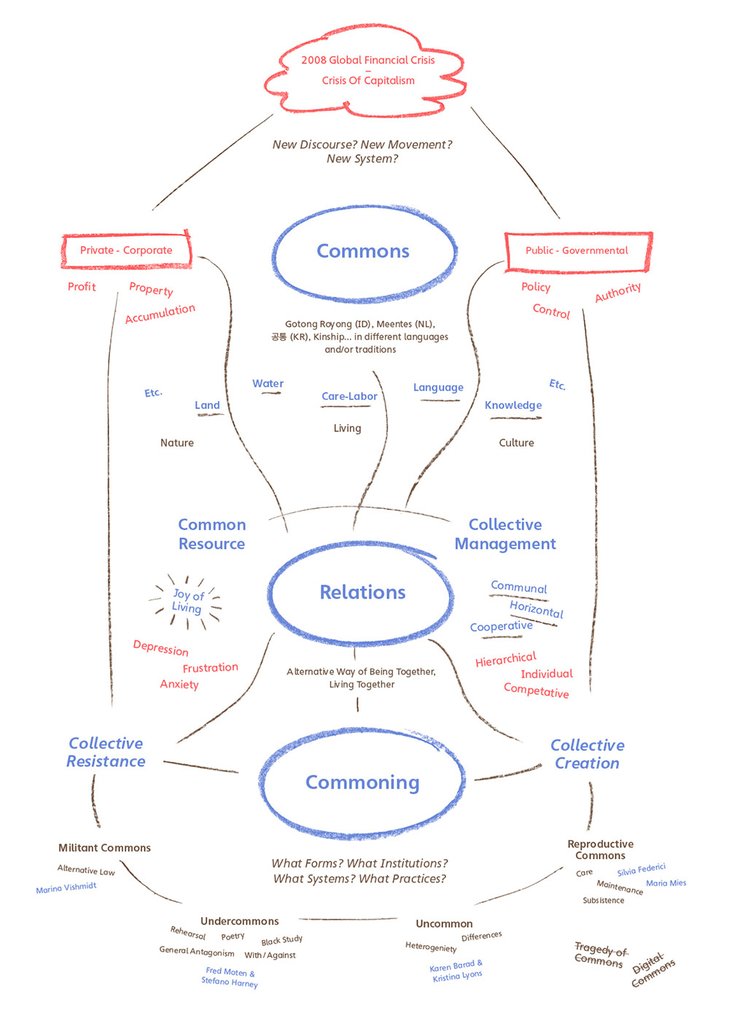

A chart for commoning the understanding of the commons (sketch 2) by Binna Choi, Illustrated by: Inherent

When we at Casco initiated this research as part of our three-year-long inquiry into the commons under the guideline Composing the Commons, we critically reflected on our way of working together in a group and/or with other self-organized communities that have been an increasingly important (and invigorating!) part of our activities. We found two interrelated focal points, sociality and economy, needed more attention, foci well-expressed in the basic tenet of the commons as voiced by prominent feminist commonist Marie Mies. Mies intimated that there’s no commons without community but equally that community cannot exist without economy. If we want to sustain collective work, it cannot be driven by an external political cause enacted only in the name of solidarity. We need to care for and foster our relations. Simultaneously this sociality also necessitates thinking of economy, yet one that is conceived in an expanded sense that includes non-monetized or undervalued forms of exchanges and relating. In other words, community and economy have to be redefined as serving the relationality of the commons.

The economy is something we do, not just something that does things to us. J.K. Gibson-Graham

A great praxis-theory work by J. K. Gibson-Graham, in particular, A Postcapitalist Politics (2006), proved for us to be a kind, illuminating guide in setting up our “business”. By saying “the economy is something we do, not just something that does things to us,” they reinstate a feminist critique of capitalist economy as propagated by other admirable feminist thinkers including our dear mentor Silvia Federici. Gibson-Graham draws attention to how the “non-economized” labor of women sustains the capitalist economy, arguing for “community economies” so as to conceive economy in a way that is as diverse and broad as possible—to such a degree that community relation is equal to economy. While this proposition may sound docile, I think it gives us a sense of agency in being part of economy, while antagonistically redefining what economy is and does when it is not ruled by capitalism.

Hence we could argue that a mode of “(un)usual business” has been taking place from the very moment of the project’s initiation, with its insistence on the practice of collective study, care, and relating with one another. However, it’s also a long-term objective to be accomplished and adopted by the enlarging communities around this area of study—that is, until we develop our own (organic) system based on interdependency among selves such that we are no longer dependent on a particular economy called capitalism. So while we celebrate the collective subjectivity we are achieving, we should also grow stronger in order to be in a position to counter “something that does things to us”!

This article was published in the (Un)usual Business journal Utrecht Meent Het #1 (May, 2015).