Dit artikel is nog niet beschikbaar in het Nederlands.

Lively District: With the development of the renewal area Kanaleneiland aims to transform the currently rundown outdoor area into a high-quality, vibrant metropolitan area. Additionally, a substantial and varied program will be integrated, which ultimately will result in intense and vivid use of public space.

Every day that passes, one can see a moving van, a container being filled up with housing leftovers, and what is named of “foreign emigrants”, leaving. // Every day that passes, one can see some “local young students” taking up an empty space, and rebuilding it, putting new curtains, opening shop.

At the Margins of the City: Kanaleneiland’s Gentrification & “Creative Commoning”

One week after I arrived in Utrecht I found myself lost, pedaling through Kanaleneiland in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to find a newly opened art commons in the area. Having recently arrived from the US, I was quite aware of the irony of getting lost on streets named “Amerikalaan”, “Rooseveltlaan”, and “Columbuslaan”. Quite adrift in this maze of colonial inspired thoroughfares, I foreclosed on my previous plans in favor of familiarizing myself with the namesakes of likewise lost European “explorers”—“Magelhaenlaan”, “Livingstonelaan”, “Marco Pololaan”, “Bartolomeo Diazlaan”, and “Vasco Da Gamalaan”. These encounters revealed to me derelict apartment blocks sitting next to buzzing construction sites; unsanctioned street art and established cultural venues side-by-side advertisements for housing corporations and construction companies. To me these visible contradictions appeared as signs of significant physical and demographic restructuring afoot in Kanaleneiland; student-, artist-, and “precariat”-led projects of creative and urban commoning projects were evidently part of these gentrifying processes. Like a vast majority of the artists, students, and “creative commoners” in Kanaleneiland, I was an outsider coming onto a tenuous, violent, and constantly shifting terrain of emerging commons—housing, resource-sharing, care-based, and creative—and enforced enclosures. And I was a factor and agent in these struggles, regardless of my intent. Many of the newly arriving Kanaleneiland residents I eventually spoke to were, likewise, “very aware that we were not walking there as empty vessels.”

To understand the interplay of commoning, enclosure and gentrification, my (Un)usual Business research focused on Kanaleneiland’s creative milieus and artistic commons. A creative presence is never innocent and never without impact: Kanaleneiland’s artists and students, as the “creative class,” are the new nationally, economically, and culturally productive and valued bodies. They are also a gentrifying presence who signal the impending enclosure of any and all pre-existing commons and commoning practices in the area. To understand this tension, I focus on the (un)usual business of “creative commons,” as well as art projects that question, interrogate, and upset these processes through creative, everyday practices. I primarily engaged newly arrived or temporary residents who, in their creative commoning practices, inevitably enable and hasten the enclosure of pre-existing community commons. Throughout this case study, I rely on their accounts and projects to look toward a more ethical, anti-capitalist artistic commons, ones that might be disruptive to the violence of displacement and state-cooptation rather than complicit in it. Overall, this research hopes to open up space for critically engaging the creative commons and its practices against the backdrop of a gentrifying city.

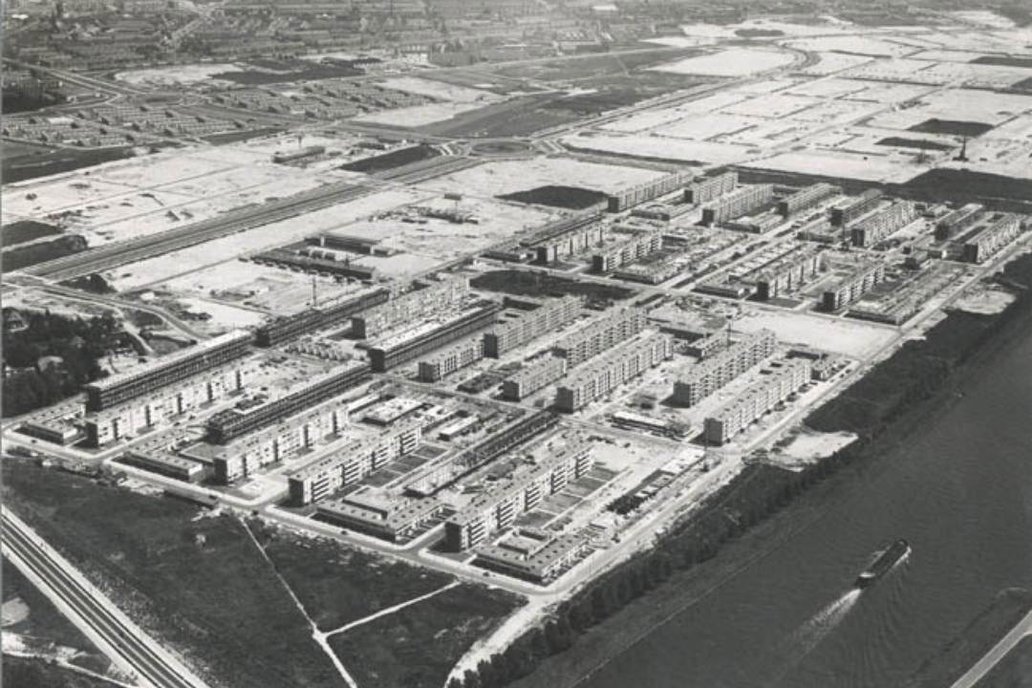

Kanaleneiland Zuid (Architectuur.org)

Kanaleneiland Zuid (Architectuur.org)

Beautifying the Margins: Understanding “Creative” Gentrification

Kanaleneiland’s creative and urban commons presents an unambiguous project of gentrifying “urban renewal”, with demographic and physical changes becoming most visible around 2009. One artist working against gentrification in the area said:

The idea was (that) we revitalize these zones in order to increase the value of the property and we speed up gentrification processes by also offering the society the possibility social consciousness; so we invite artists to occupy temporarily a location and speed up the gentrification process.

As in other Dutch cities, the municipality of Utrecht worked with housing corporations to offer students, artists, and “creative commoners” the role of “keeper(s) of the aesthetic and symbolic quality of the public space, but also … the opportunity to make \[their\] mark, at an early stage, on a future piece of central urban domain.” Architects, designers, and multimedia artists are subsequently tasked with mobilizing their creative energies toward creating state- and capital- supported common spaces. Eiland8, in partnership with housing corporations renovating and building in the area, helps guide this input; it leases cheap studio spaces to students and artists, while distributing considerable money to their creative projects. These grants are based on the voting of residents, targeting the young artists and students streaming into the cheap, temporary housing in the area. Several of the residents I talked to pointed out that this “democratic” process was tightly controlled by Eiland8, which is itself funded partly through monthly resident contributions:

Part of your rent went to this (housing company) organization that was meant to bring people together, make the neighborhood better and definitely to give the neighborhood a better look. You know, gentrification sort of things. Part of our discussions, as activist artists, were a critique of this organization.

The Utrecht municipality, given to branding the city as “the most innovative, talent-rich and creative city in The Netherlands,” is likewise prone to see creative commoning practices as a way to lessen the direct impact of economic and housing crises,’ as well as recent cuts to social services:

Someone behind a desk came up with the idea that (Kanaleneiland) had to be a creative city… and we were the ones who were organizing and making stuff but they were kind of working against us … but it was mostly important that it created good publication/publicity, while we just wanted to do good stuff for ourselves and our neighbors.

Additionally, the public-private partnership between the municipality and housing corporations is indicative of a general trend in contemporary Dutch urban and creative policy:

What is happening in the Netherlands because of the budget cuts in culture is that artists are expected to fill in the gaps … geographical gaps, but also on a meta-level, in places where the state has failed in producing something very concrete.

Many of the artists I spoke to were also activists critical of these public-private partnerships, organizations like Eiland8, and the overall gentrification they saw implemented in Kanaleneiland. No one was naively claiming that these transformations were not occurring, or that they were positive in nature. One resident, who had lived in the area since 2010, recounted that when she first moved in,

there were always people outside. … Also everyone would dumpster dive. … The experience of walking or biking through the neighborhood really changed over the years because at first there would be a lot of people outside. Then Turkish and Moroccan families moved away and there were much less people in the streets because the new Dutch artists didn’t want to hang out there. … At first my neighbors were really looking out for people, checking with each other, calling each other out if there was too much trash or noise … I felt there were people watching out for us and that made us feel safer. Now after several years, all these people have moved away.

Another artist, involved in the anti-gentrification project locatie:KANALENEILAND, spoke to the necessity of critically and creatively engaging the processes that power gentrification:

It is a process of city transition. You cannot really overlook it, you cannot really fight it, but you can work around it in order to create a more sustainable way of how things are implemented and how you position yourself within it … this is what we were trying to inspire people to do, looking at gentrification not as the enemy but as something you can position yourself within, and try to have a more sustainable way of how things are done, because it’s going to evolve and change anyhow.

locatie:KANALENEILAND was part of a larger creative project by Expodium, an Utrecht-based political arts collective whose work has engaged gentrification and creative practices in both Utrecht and Detroit, Michigan. The project applied for, and was granted, an apartment by the creative agency partnered with Kanaleneiland’s housing corporations; they used this space to establish a residency for artists that began in mid-2011. In addition to creative events held in the apartment, the project built an unapproved porch onto the property to create a common meeting and social space. They also partnered with artists and activists already present in Kanaleneiland to turn their informal nightly walks into NIGHTWALKERS. This endeavor was organized around various themes, and aimed to inspire “various formulations of agency and bottom-up responses to gentrification.” One of the organizers of NIGHTWALKERS recounted:

We always invited people from the neighborhood because the whole idea initially was that you look at the neighborhood but through other eyes … still at that time people thought it was scary to walk around, there were still a lot of mixed groups living there, some people were catcalled a lot … so it was an idea of walking together. It was also a dynamic of getting to know people.

These walks inhabited public spaces that had been rendered mostly deserted, especially at night, by the displacement of Moroccan and Turkish families in the years prior. The NIGHTWALKERS also attempted to establish a relation between people within common spaces, as well as between residents and the physical geography of the neighborhood itself; these “creative commoning” relations, building off of everyday encounters between bodies and physical space, speak to locatie:KANALENEILAND’s approach to gentrification:

What we were trying to do is to try to stimulate people into thinking differently and subsequently act differently than was it happening with gentrification in any way possible. For example, from skateboarding in the middle of the street, or aerobics classes underneath the bridge, to communal dinners. It is not necessarily political in the strictest notion of the word but it addresses politics and the commons in a broader sense. And it is accessible to everybody not as an art performance or art event … but this needs insane amount of work and a rethinking of strategies and practices to develop a language that is accessible to people.

The residency ended in 2012 and resulting publications detail the project’s work. The porch remains but the surrounding terrain continues to change quickly and drastically, both physically and demographically. The cheap housing, increasingly visible creative projects and cultural venues, and a developing reputation as an “up-and-coming” neighborhood continue to draw the precariat to Kanaleneiland for now. Through these processes of urban restructuring, the municipality plans to shift the future city center towards Kanaleneiland; it is thus unclear how long the area will remain a “safe haven” for artists, students and creative commoning.

Centering “Problematic” Subjects: Creative Commons as Enclosures

Commons theorist Silvia Federici has argued that commons posses a “potential to create forms of reproduction enabling us to resist dependence on wage labor and subordination to capitalist relations.” However, the most visible creative commoning in Kanaleneiland is produced through/around art spaces and critical, creative projects like locatie:KANALENEILAND; many of these projects are supported financially or nominally by both capital and the state. As such, these commoning practices are positioned at an illuminating point within (and between) contemporary processes of primitive accumulation and anti-capitalist resistance to these forces. Most importantly in regards to the former, art spaces and “creative class” consciousness play particular roles in engendering gentrification as a new form of primitive accumulation: they assist private capital directly and indirectly with enclosing pre-existing common spaces (and resources) deemed “problematic” by the state.

In Kanaleneiland, this particular accumulation is evidenced in a 2007 law supported by the city of Utrecht and private housing corporations. Though it was later deemed unconstitutional, this law banned public assembly in parts of the neighborhood, prohibiting more than four people from gathering publically. In service of the newly arrived population, this law foreclosed on (a) commons not approved or recognized by the Dutch state or capital interests. A commons autonomously cultivated and inhabited by the previous inhabitants of Kanaleneiland—mostly immigrant and first-generation working class Turkish and Moroccan families—was too “problematic,” too threatening, to be allowed to endure.

locatie:KANALENEILAND’s porch project can be seen, in this light, as an attempt to intervene in the ongoing enclosure of public space. The porch provided a physical point for socializing and loitering despite the general antagonism towards young Moroccan and Turkish men inhabiting common spaces. This attempt, however, was dampened by the new population’s reliance on the state and on police to “safeguard” public and private spaces. Rather than becoming a respite from the increasing police surveillance and harassment in the area, the porch project further illuminated the tensions around different conceptions of common safety, racism and xenophobia in Kanaleneiland. In reality, those “problematic” young Turkish and Moroccan men were no safer on the porch than they were down the street. In fact, given the high likelihood of engaging with newcomers likely to call the police if they felt “threatened,” many youth avoided the porch and the surrounding area while the project was active.

Through my research I spoke to a youth worker from the area about the porch; she recounted that after locatie:KANALENEILAND left the space the porch was maintained as a point of socialization for youth in the neighborhood. Many of the older youths, who previously felt surveilled or unwelcomed, also began to socialize near or on the porch. Still, this case makes clear that Kanaleneiland’s pre-existing common culture of care, safety and socialization has always been in direct tension with emerging creative commons and artistic practices. For the most part, these unintelligible or obscured commons have subsequently been destroyed by the surveillance and harassment of a racist and xenophobic “security culture.” Prevalent amongst the newcomers without any community ties, and couched in the rhetoric of Kanaleneiland as an unsafe, “problematic” neighborhood, this securitization has evolved a new culture where “the cops are called quite easily.”

Urban(e) Commoning: Cities as Creative & Cultural Commons

Through their daily activities and struggles, individuals and social groups create the social world of the city and, in doing so, create something common as a framework within which we all can dwell. While this culturally creative common cannot be destroyed through use, it can be degraded and banalized through excessive abuse.

Kanaleneiland’s creative commons exist in critical relation to the play of state and capital forces that power enclosure, foreclosure, and gentrification processes. While it now contains an ever-growing creative class of students, artists, and young “precariats” drawn by cheap rents and state city planning programs, Kanaleneiland was built in the 1960s as a model neighborhood. Architecturally planned as a productive “commons,” its physical spaces were designed for individual privacy, consumerism, and productive labor. Structurally, the community’s housing, work, and shopping were physically separated but immediately accessible, promoting the conception of Kanaleneiland as a self-sufficient neighborhood. When these initial residents left, the Dutch middle-class was replaced by mostly working-class, first- and second-generation Turkish and Moroccan families. These communities began independently reutilizing these spaces in non-state-supported commoning practices. As marginalized, surveilled and so-called “problematic” communities, they were (and are) much less likely to rely on the police or state agencies for social services, support and safety. In many cases these governmental institutions of social “betterment” and community welfare enable further oppression and marginalization migrant populations. As in many places, this resulted in various forms of commoning practices and mutual aid emerged to support the community without state involvement. To further investigate the overlapping of urban commons in neighborhoods like Kanaleneiland, in this section I address the various thinkers who contribute to the figuring of the city as an urban, cultural, and creative commons.

In this section’s epigraph, David Harvey articulates a materialist (pre)figuring of the city as a culturally creative common. He likewise points to a potentially productive dissonance in the charged and contradictory relation between the commons and processes of enclosure. In this framing, protecting non-commodified and anti-capitalist commons might necessarily entail some form of “enclosure”, as would a community’s demand for local autonomy from the state. However, Harvey’s urban commons is more than just a contested physical space, or a non-commodified ethic of caring and sharing through communal (re)production. The commons is more than demarcated land, or even a social or cultural process. Rather, a commons is “an unstable and malleable social relation between a particular self-defined social group and those aspects of its actually existing or yet-to-be-created social and/or physical environment deemed crucial to its life and livelihood.” In other words, all of the interpersonal relationships crisscrossing diverse urban landscapes (pre)figure the city commons, and our “social practices of commoning” are as integral to the commons as a defined location. In Revolution at Point Zero, Silvia Federici similarly envisions this relation as an activity of producing common subjects, where “no common is possible unless we refuse to base our life, our reproduction on the suffering of others, unless we refuse to see ourselves as separate from them.” To this point, one artist active in NIGHTWALKERS spoke to the necessity of maintaining stable and open interpersonal interaction as a basis for commoning relations:

There was not a clear control of who is entering this zone, who is getting these apartments and what are their responsibilities . . . also it creates this problematic of how you expect art to be the mechanism for creating social cohesion when it’s already completely broken down and then additionally dismantled by you moving people to other places, but it definitely creates mistrust and so forth.

In this case, the constant material changes brought by gentrification—from the temporary nature of housing to the ongoing displacement of Turkish and Moroccan inhabitants—helped to forestall possibilities of enmeshing the new creative commoning practices with pre-existing social commons in Kanaleneiland.

The commons is also (pre)figured as a site of immense creativity and cultural (re)production. Harvey cites Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s Commonwealth, where the theorists proffer a cultural commons that is “not only the earth we share but also the languages we create, the social practices we establish, the modes of sociality that define our relationships, and so forth.” Assisted by the production and spread of knowledge via technologies of advanced capital, such a commons would be plentiful and expand over time, offering a commons of abundance. But in her critique of their argument, Federici posits that—in line with most of the contemporary theorizing of “the commons”—Hardt and Negri focus on establishing the preconditions for new commons rather than looking to existing commons for possibilities, tactics, and strategies. In doing so, they overlook the material relations that form the basis of their ever-expanding cultural commons—the labor, technologies, and transnational flow of knowledge/capital on which it depends. Federici also takes them to task for ignoring the integral aspects of the reproduction of everyday life upon which all commoning activity rests. In the context of Kanaleneiland, Federici’s critique of Hardt and Negri illustrates a resonant tension in contemporary theorization about the commons: the erasure of existing social/care/reproductive commoning practices in favor of new, exciting, and utopic “emerging” commons.

One might wonder where all this commons theory meets actual commoning practices. To follow Federici’s thinking, creative and cultural commoning must address (and be accountable to) the material and social relations of gentrification, in terms of both the processes of enclosure and in the emergence of new, especially “creative”, commons. This story is not new, nor is it unique to Kanaleneiland. It begins with spunky young upstarts searching for affordable shelter to house their precarious lives and forms of artistic (re)production. This “creative class” often lands (through state directive or financial need) in historically working-class neighborhoods populated by communities of color, migrant workers, asylum seekers, and refugees. In conjunction with capital (rent/food price increases, the commodification of social/care relations) and state (proliferation of private surveillance, community policing, and city “safety” measures) forces, new creative commoners then displace supposedly “less creative”, “problematic” residents. Like Kanaleneiland, such neighborhoods almost always already contain a pre-existing commons, along with a multiplicity of unfixed and evolving commoning practices emerging out of the shared burden of reproducing the social and cultural life with little to no state or financial support. Often reliant on the invisible care labor of women, queers, children, and the elderly, these invisible commons are integral to what Maria Mies, pulling from Karl Marx, calls the “production of immediate life”: a feminist concept of work “oriented towards the production of life as the goal of work and not the productions of things and of wealth.” This is also what Federici alludes to when she cites Mies’s slogan “no commons without community”: “Community as a quality of relations, a principle of cooperation and responsibility: to each other, the earth, the forests, the seas, the animals.”

Some of the creative projects questioning gentrification that I looked at took up this call, attempting to engage pre-existing community relations as a basis for new commoning practices. But most emerging creative commons seek to create their own, new, artistic community relations, which are at times formed in direct opposition to the people already residing (and commoning) in gentrifying neighborhoods. These tendencies explicate an ongoing tension around ethical commoning in an era of state co-optation/deployment of “the commons”—what would it look like to creatively common with an awareness of all the other commoning practices already in play? Or, perhaps, how to cultivate creative and ethical commoning practices that might traverse, link, or weave multiple kinds of commons and methods of commoning? What kinds of art practices engender movement toward an accountable commons? To this end, in the words of one Kanaleneiland artist, how might creative caommoning practices “stimulate people into thinking differently and subsequently act differently … about gentrification in any way possible?”

Insurgent Marginalities: Towards a Creative (Under)commons

“In the undercommons . . . this ongoing experiment with the informal, carried out by and on the means of social reproduction, as the ‘to come’ of the forms of life, is what we mean by planning; planning in the undercommons is not an activity, not fishing or dancing or teaching or loving, but the ceaseless experiment with the futurial presence of the forms of life that make such activities possible.”

Gentrification processes (in name) aim to “revive” and “diversify” the physical, financial, and demographic landscape of certain communities. They succeed by (at times violently) enclosing on the diverse pre-existing social/spatial relationships of the city commons, on our infinitely possible intimate and daily relations, and on our accountability to one another in a shared time and space. To this point, I’ve questioned what tools (or toys) we need to explore how to prefigure a creative commons while also being accountable to pre-existing commons. While I cannot offer adequate answers in the space provided, I find Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s The Undercommons a salient concept that, along with such questions, might help negotiate a more responsible elaboration of creative commoning.

The Undercommons interrupts the primacy of an explicitly defined politicized, anti-capitalist commons, with an implicit/assumed population of mostly white, masculine, heterosexual, Christian commoners. Harney and Moten offer the “undercommons” as a conceptual shift “to develop a mode of living together, a mode of being together that cannot be shared not as a model but as an instance.” This articulation of an “undercommons” is situated within a genealogy of Black radicalism heretofore ignored by almost all major theorists of the commons. Harney and Moten’s explication of the “undercommons” extends this Black radical tradition, exposing and celebrating the affective insurgency and forms of mutual aid “common” to black life/lives across time and location. This conception of an “undercommons” importantly highlights a complete erasure of race and ethnicity from most of the dominant theorizing about the commons.

The Undercommons presents a valuable shift in creatively thinking-through the “commons” as something—a feeling, a movement, a “mode of living together”—that is always already present, though it is often invisible to those outside its affective reach. In this turn, Harney and Moten speak directly to the cooptation and enclosure of gentrification processes, pointing out that as soon as a commons is publicly recognized or acknowledged, its regulation (and thus cooptation) is inevitable. Even tactical resistances to enclosure “can only be a politics of ends, a rectitude aimed at the regulatory end of the common.” The value of centering a purposely (un)figured “undercommons,” one that is “already here, moving … more than politics, more than settled, more than democratic,” one that “surround democracy’s false image in order to unsettle it,” is precisely that its radical potential cannot be coopted or deployed by capital and state interests.

In the “undercommons” of Kanaleneiland the “planners”—both the “problematic” Turkish and Moroccan youth as well as the students, artists, and “precariats” employed in the neighborhood’s creative revitalization—“are still part of the plan. And the plan is to invent the means of a common experiment launched from any kitchen, any back porch, any basement, any hall, any park bench, any improvised party, every night.” As the authenticated “planners” of the future creative and profitable Kanaleneiland, “creative (under)commoners” have direct access to the resources supporting the planned renewal of their neighborhoods. Appropriate them, redistribute them, use them to plan: such resources could be adapted to support an unsuspected “common” insurrection against gentrification, an “up/downrising” inspired by, and waged from, an unseen “undercommons.” The unauthorized, so-called “problematic” “planners” must also strategize, must also plan and be part of the plan; and in their unintelligibility they might transform the “problematic” into the “crisis” needed to disrupt or stall processes of gentrification. In the ordinary, every-day interactions in Kanaleneiland, the “planners” can plan in ways that defy the notion of “planning,” and explode normative notions of what is “creative” and what is “common”. And in any struggle against seemingly insurmountable forces, the use of unauthorized and unrecognizable tools, toys, and concepts is always a plus.

The varied and seemingly mundane relations, encounters, and instances of the “undercommons” reveal a potently radical pre-/un-figuring of creative commoning. Rather than bringing pre-existing “undercommons” into the realm of recognition, creative commoners might do well to think downward into the affectively insurgent, always ready, and ever-unintelligible “undercommons.” Once the development plan for Kanaleneiland is completed, most of the current creative commoners, especially those with anti-/non-capitalist sentiments, will become the new surplus population targeted for displacement. The commons they have created will continue to maintain the area’s creative and cultural “authenticity”. Some of creative commoning surveyed here points to a fomenting simmering, a potential new mode of being together, and the beginning of a insurrectionary, creative (under)commons; but what else might be done to interrupt, to trip, to displace the use of creative commoning as a mode of gentrification in Kanaleneiland (and elsewhere)?

Looking to “undercommoning” as a mode of being together, a “creative (under)commons” demands myriad experiments with the seemingly banal or mundane aspects of our daily lives—from reproduction to total destruction—across scattered visible and hidden relations, and between diverse peoples, physical spaces, and affective powers. This experimental relationality demands that creative (under)commoners be accountable to the omnipresent legacies of slavery, colonialism and economic imperialism. In order for a creative (under)commons to manifest un-mired by colonial white supremacy, patriarchy, heterosexism, xenophobia, ableism, and the like, those commoners who are the beneficiaries these systems of repression and control must also actively work to destroy them. A creative (under)commons requires this critical work and self-reflexivity, and it also thrives through an infectious, affective and joyful consciousness. Indeed, this is its threat. The creative (under)commons persists as an ultimately hopeful place: it both looks towards un-figured radical futures and gestures towards more accountable and situated commoning practices in the present.

This entangled force of the (under)commons urges creative commoners to plan around, through, and against gentrification processes, as well as the forces mandating this violent accumulation. Here, in the commonness of night walks, porch communing, collective consumption, and community security, the possibilities of creative (under)commoning might be seen—they might even multiply. To avoid replicating gentrifying commoning practices, the creative (under)commoners to come must be prepared to study, to plan, to pre- and un-figure, and in all this plotting create a insurgent common relation that might begin to unweave the abiding bonds between gentrification and creative and artistic commoning practices:

Before someone says let’s get together and get some land. But we’re not smart. We plan. We plan to stay, to stick, and move. We plan to be communist about communism, to be unreconstructed about reconstruction, to be absolute about abolition, here, in that other, undercommon place, as that other, undercommon thing, that we preserve by inhabiting. Policy can’t see it, policy can’t read it, but it’s intelligible if you got a plan.

OKRA Landscape Architechts, “Kanaleneiland Centre,” OKRA, (accessed 10 February, 2015).

João Evangelista, “Part 1, first days: On Nostalgia, Decay and the Absence of Reason,” locatie:KANALENEILAND, 16 September 2011, (accessed 10 February 2015).

The term “precariat” is a neologism combining “precarious” and “proletariat” referring to an emerging class of precariously, temporarily, and under-employed members of the working class. It also indicates individuals who, due to economic crisis and sometimes choice, are employed in jobs below their education level. See also, Guy Standing, “Defining the Precariat: A Class in the Making,” EUROZINE, 14 April 2015, (accessed 12 February, 2015).

The term “gentrification” was coined by sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964 to describe the economic, demographic, commercial, cultural, and material changes brought by urban “revitalization/renewal” projects: Glass observed that “The social status of many residential areas is being ‘uplifted’ as the middle class—or the ‘gentry’—moved into working-class space, taking up residence, opening businesses, and lobbying for infrastructure improvements.” Japonica Brown-Saracino, “Gentrification,” Oxford Bibliographies Online, (accessed 10 February 2015).

Kanaleneiland, artist interview, 2014.

Bavo, “The Dutch Neoliberal City and the Cultural Activist as the Last of the Idealists,” (accessed 5 February 2015).

See eiland8 website.

“Investing in Utrecht,” Utrecht Municipality Online, (accessed 5 February 2015).

According to the documentary blog of the project, locatie:KANALENEILAND’s “physical space is located in an apartment at the Auriollaan and is set to function as a roof for a series of activities organized by invited artists, neighborhood initiatives and organizations…. By putting the apartment at the Auriollaan into use, Expodium commences a project that constitutes itself as a creative agent and critical voice within gentrification processes carried out in the area.” Artists were invited to do one week residencies, document their work and process, as well as participate in ongoing projects like NIGHTWALKERS and events held at the Auriollaan apartment. See the project’s work and documentation at locatie:KANALENEILAND blog.

Expodium is the art collective that created the locatie:KANALENEILAND project. They state that, “through a variety of methods of artistic research, we generate vital information about urban areas and at the same time activate those areas and their users.” More information about the collective here.

For more on NIGHTWALKERS see “NIGHTWALKERS Kanaleneiland, Are You People?” published by Expodium, available here.

“locatie:KANALENEILAND” publication by Expodium available here.

Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012), p. 142.

“Court Slams Preventative Arrest of Youths Gathering in Public,” EXPATICA, 14 February 2008 (accessed 10 February 2015).

Kanaleneiland, artist interview, 2014.

David Harvey, “The Future of the Commons” Radical History Review, no. 109 (2011): p. 107

David Harvey, “The Creation of the Urban Commons,” Rebel Cities (New York: Verso Books, 2012), p .73.

Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero, p. 145.

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Commonwealth (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 139.

Maria Mies, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale (London: Zed Books, 1986), p. 217.

Federici, Revolution at Point Zero, p. 145.

Kanaleneiland, artist interview, 2014.

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (New York: Minor Compositions, 2013), pp. 74–75.

Ibid., p. 105.

Ibid., p. 18.

Ibid., p. 19.

Ibid., pp. 74–75.

Ibid., p. 82.

Dit artikel is gepubliceerd in het (Un)usual Business journal Utrecht Meent Het #1 (mei, 2015).